Scientific background of Mindfindr

This article discusses the development process of Mindfindr and exemplifies some uses of the service. The central psychometric features of the service are presented, as well, so as to help client organizations assess the usability and validity of the service. Some concepts relevant for evaluating the validity and quality of any psychological instrument are touched on in the said purpose. Finally, the practical usage of the method is discussed and the components of Mindfindr results reports are introduced at the end of the article.

Markku Nyman

Mindfindr Ltd.

2020

Introduction

Mindfindr has been developed using research methods typically utilized in psychological service development based on relevant psychological concepts and models. A pivotal idea related to practical psychological methods like Mindfindr is that there are psychological differences between individuals and these differences affect how individuals fare in various professions and occupations. Differential psychology studies these individual differences and aims to understand and explain how these differences in personality traits, competencies and aptitudes are related to success in various professions. Work and organizational psychology is a natural application area of differential psychology, as it stands to reason that both organizations and individuals benefit if employees find those niches in the market where to best apply their relative strengths. On the other hand, organizations demand certain kinds of competence potential for their production processes. Similar laws of supply and demand function in the labour market as in other economic markets. Psychological service solutions are used to make the supply and demand of human resources better match in the market.

Theoretical background of the Mindfindr assessment service

Where does Mindfindr stand in relation to scientific philosophical positions?

Psychology as a scientific endeavour may be placed at the intersection of the natural sciences, the humanities and social sciences. The effects of these neighbouring sciences and research traditions become differentially evident depending on the focus of psychological research. Additionally, there are different schools of thought inside psychology, and they may not share all of their basic assumptions about human behavior. Work and organizational psychology relies also on the findings of economics and administrative sciences, as well as on social psychology in its mission of serving organizations’ needs concerning the optimal matching of individual potential and competence requirements of firms. In addition, swift progress in neuro-scientific studies has strengthened the foundations of personality psychology. Worthy of mention are also sociological and cultural studies, for their significant contribution in helping globalising organizations to better understand cultural differences.

Regarding scientific-philosophical positions, with ontological and epistemological considerations more specifically in mind, the developmental process of the Mindfindr service may be placed in the sphere of pragmatism, or little more specifically in the domain of realistic pragmaticism. The service has been iteratively developed, by utilizing empirical data, realistic criteria as well as interviews along with more traditional correlative methods. The fundamental principle in instrumentalism, that is akin to pragmatism, is to consider theories, models and methods as useful and practical instruments to the extent they serve the set purposes in practice. Hence the characterization of the approach as instrumentalism. In work and organizational psychology, the usability and practicability of any method, a test or another kind of instrument, boils down to how much they increase our understanding and information about the compatibility of persons and position-related competence requirements.

Reliability of psychological methods

When evaluating the validity and reliability of a method it is necessary on the one hand to take into account certain basic considerations relevant in any scientific measurement. On the other hand, we should consider some general issues related to measurement of human behavior and especially some problems related to predicting work behavior. In scientific measurement the idea is to gauge a phenomenon of interest as reliably and exactly as possible. In psychology we usually refer to phenomena we measure as constructs or concepts that have first been substantially defined and then operationalized so as to make them empirically measurable. The process of operationalization aims at defining the construct or concept of interest so that it’s incidence in practise may be statistically measured using empirically produced data. The rationale behind the procedure is thus to find out if the defined phenomenon occurs in reality the way the construct predicts or presupposes. In order to really make robust inferences about a method and hence to state something about the quality - that is e.g. reliability and validity - of the method, we should be able to collect information from many individuals. Due to certain things later discussed in the text, even a method that was shown to produce qualitatively high results on average, might give widely differing test results at the level of individual research subjects.

This so called error variance is brought around to an extent by individual research subjects possibly having either intentional or unconsciously affecting interest to respond to test items in certain ways, besides various random effects that affect test outcomes and that are usually more important sources of this error variance. The Mindfindr service takes into account these kinds of error variance sources the same way as other established personality inventories (The NEO-PI, The Prf, Big Five instruments, The MMPI).

The phenomena that are studied in psychology show in behavior for instance as acts, motives, emotions and thoughts. If the presence or incidence of these forms of behavior is not confirmed by conventionally utilized statistical rules when applied to analyse and test collected empirical study data, there is no other way to verify such constructs, and they are rejected. Sometimes constructs may not be operationalized for empirical scrutiny at all. Such phenomena may appear subjectively real for individuals even though we cannot find ways to verify their objective existence according to scientific principles. There is no denying subjective feelings, while we usually can measure empirical correlates of objective phenomena. Objective reality and subjective experiences may differ, as science looks into the invariance in phenomena, while subjective minds are affected by many such phenomena that cannot be controlled for research purposes. In psychological tests research subjects and persons being assessed are presented operationalized constructs in forms of test items, questions, statements, or problems to be solved. These yield information about the mood, dominance or other needs, as well as general cognitive aptitudes or for example linguistic abilities of the assessed, among other things. The so called face valid tests consist of items whose relation to the constructed domain of behavior that is measured becomes evident to research subjects taking the test. There are also tests in which the relation to the measured phenomena is not evident or straightforward in nature. In these instruments the relation between the visible behavior the test predicts and the test items representing the construct is mediated by other psychological information. The Mindfindr test makes use of both kinds of test items.

Owing to the nature of psychological information, psychological methods do not yield as exact or probable information as natural sciences like physics and biology. However, in any measuring, results are analytically composed of two components. Besides a component measuring the studied phenomenon more or less exactly, there will be another component that includes many different kinds of random effects. However, when evaluating the usability and validity of a method, it is important to realize that there will also be real changes in the psychological properties and traits of individuals, irrespective of these potential random measurement errors. These changes may differ with the length of intervals between measurements, and also with the age of assessed persons. Genuine error variance in measurements is caused on the one hand by situational factors affecting the testees’ responses and on the other hand by such behavioral factors that may not be easily controlled even though they affect the way tested persons relate and respond to test items or solve problems (motivation, interests, mood, alertness or energy levels). When using the same instrument to measure behavior multiple times it is useful to understand that the more time has elapsed between measurements the more likely it is that the results differ to an extent, solely because of the plasticity of the neural system, this change showing also in the personality of the assessed. It is not rational to think in the light of evolutionary psychology that human behavior and personality features are cut in stone. Individual adaptations to new experiences over the lifespan lead to maturing and learning. This is reflected in the personality and behavior of the individual.

Worthy of consideration are also various error variance sources related to societal and possibly even global circumstances and changes in them that may affect how the testees interpret test items and respond to them. Self-evident sources of error variance are practical circumstances when not controlled. This category includes such factors as test-room facilities, temperature, time of day, potential distractions like noises and the like. Besides various motivational factors and fleeting moods individuals may also have differing interests related to giving information about themselves. When validating test instruments, it often proves difficult to arrange test sessions on multiple occasions for the same persons with unchanged interests regarding their being tested and giving information about themselves. This is a reason why reliability information on psychological instruments and test methods based on test-retest procedures is sometimes hard to find. The quality of psychological test methods is composed of the exactness and accuracy, or in more technical terms, validity, of the instrument, this referring to how well the method measures the construct and phenomenon it is supposed to measure. Another consideration regarding the quality of an instrument, and in fact a prerequisite for validity, is the reliability of the method. This term refers to how similar results a test gives when used multiple times to gauge the same construct in the same research subjects.

In more general terms we may discuss the trustworthiness of a method, which may be affected by the scientific reputation or academic competence of the test developers. Similarly, when evaluating research results, we may want to know about who sponsored that particular research project, as their interests may have affected what kind of questions were used and for what political or other purposes. Even more generally, scientific-philosophical positions adopted by the evaluators may implicitly or explicitly affect to what extent a certain research method is deemed trustworthy, reliable or relevant.

A person who has adopted a relativistic or social constructionist view might argue that there is no such human essence that could affect let alone determine an individual’s behavior independently of free will. Various philosophical views on the world, the human being and our existence thus affect a great deal to what extent we consider psychological information reliable, scientifically valid or as trustworthy knowledge to start with. Taken to an extreme this means that the usability and worth of scientific endeavour are questioned as meaningful activities.

A person who accepts scientific and psychological idea of man is likely to consider information produced using psychological instruments credible to an extent the above introduced reliability and validity criteria are met. Still, it is important to remember the reservations related to measurement of human behavior. Despite the rapid development of neuroscience and genetic research that contribute to psychology, we cannot compare psychological findings with natural science results where their exactness is concerned. When contrasted with the behavior of other primates human behavior is very much affected by cultural effects. Also various social processes seem to be more complicated in humans than in other primates. There is hence no rational comparing psychological findings with those discovered in hard sciences.

The quality of research and reliability of methods

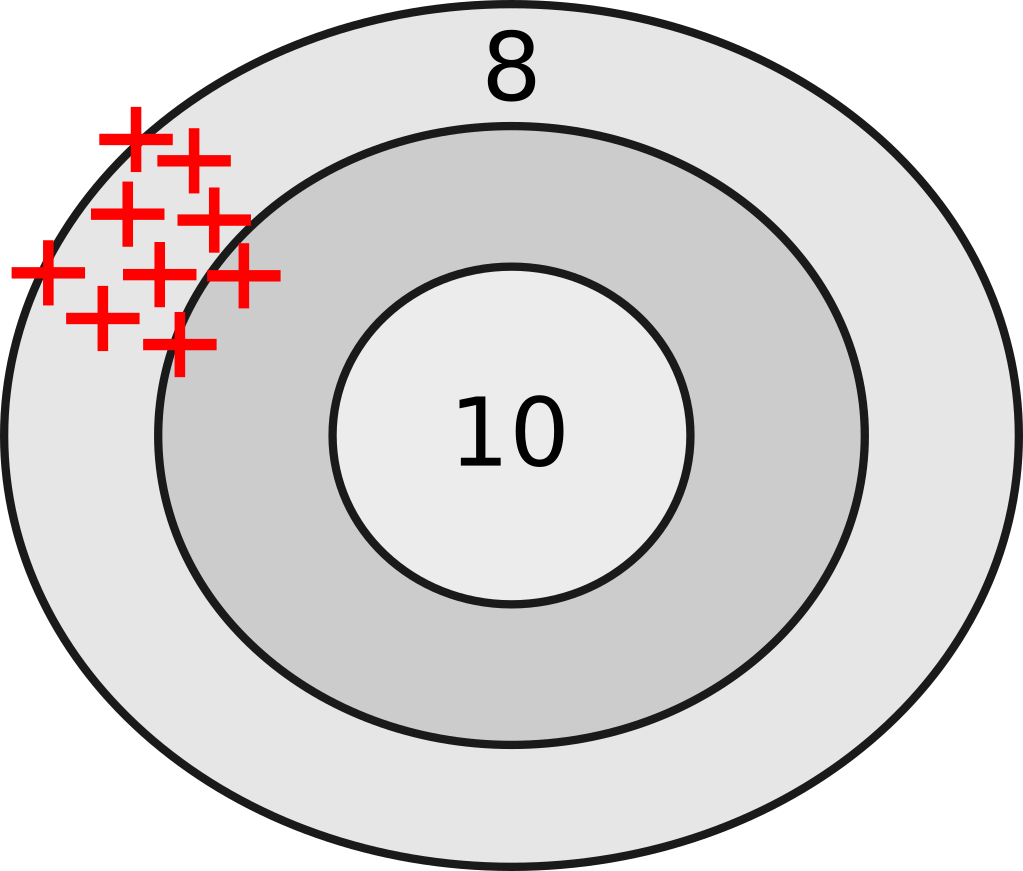

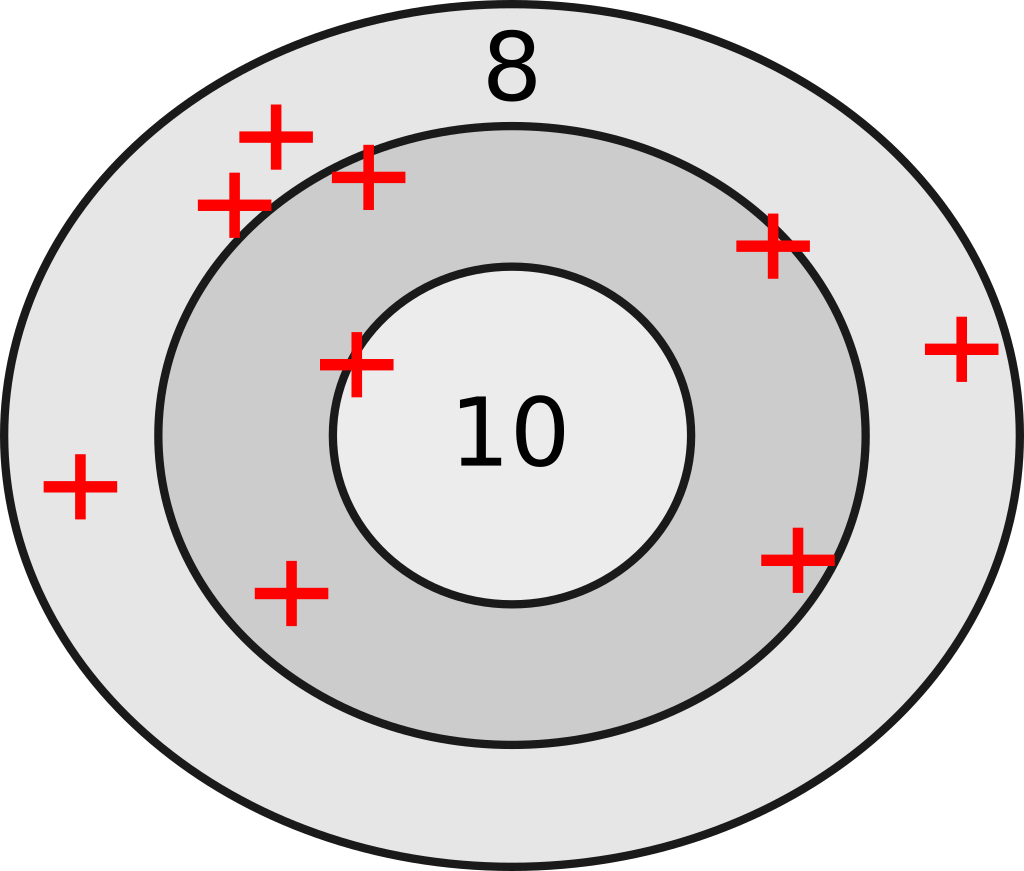

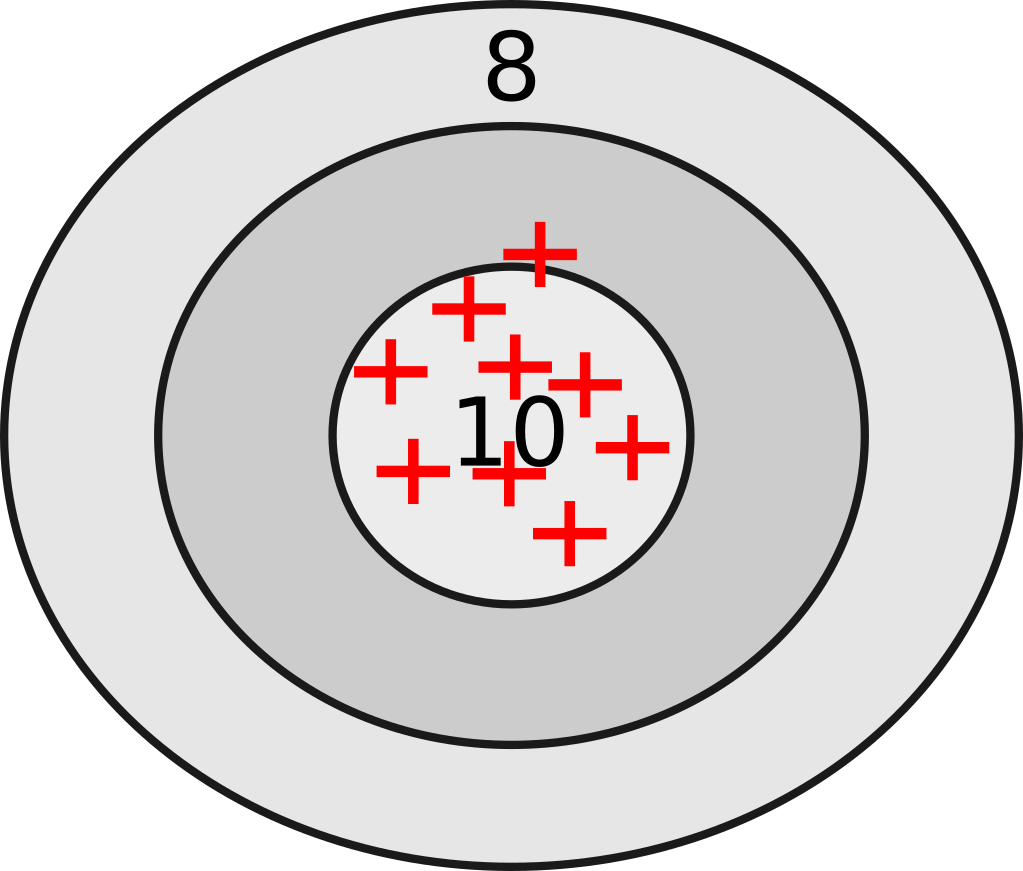

The quality of psychological research processes, and especially the reliability and validity of used instruments may be illuminated with the help of the well known bull’s eye analog. Whereas a bow or a firearm is said to be good if the arrows or shots hit the center of a target, a psychological instrument is considered reliable if it gives similar results over a series of measurements. We cannot consider an instrument reliable, let alone valid and useful, if it gives different results in repeated measurements in otherwise similar conditions on the same research subjects.

Figure 1 depicts results given by a reliable but inexact and hence invalid instrument. The hits are in a tight cluster but wide of the target center. Another consideration is the validity of an instrument. Metaphorically this means that the arrows land where they are supposed to hit.

Figure 2 presents results given by an unreliable instrument. The hits are on average on the target but still scattered around the center. Since this method is not reliable, it is impossible to assess its validity either.

In order for an instrument to be valid it has to be reliable. Valid instruments give results that hit the center of a target, the bull’s eye. Reliability and validity of an instrument or a method may be approached from various perspectives, while reliability is a primary consideration when assessing the quality of an instrument. There are two basic ways of assessing reliability.

- Internal consistency: to what extent different items of a test instrument measure the same operationalized phenomenon.

- Test-retest reliability: to what extent different measurements on the same subjects yield stably similar or the same results.

Test-retest reliability of an instrument is a self-evident requirement for any psychological test while often being difficult to ascertain due to reasons discussed above. Internal consistency is to an extent perhaps more debatable criteria of reliability. Both these criteria are technically evaluated based on the correlation coefficient, that is one of the most widely utilized statistic. The correlation coefficient is a statistic that describes simultaneous varying of two variables, showing to what extent these are linearly related in their variation either positively or negatively. A perfect positive correlation (+1.0) means that a one-unit change of a variable into a positive direction is related to a one-unit change of another variable also into a positive direction. In an imaginary psychological experiment on human perception we could have a test result where the age of the subjects and the ability to make correct perceptions in a certain time limit correlate as follows:

| Age | Correct observations per time |

|---|---|

| 18 | 72 |

| 20 | 71 |

| 22 | 70 |

| 24 | 69 |

| 26 | 68 |

| 28 | 67 |

| 30 | 66 |

| … | … |

Table 1. An imaginary example of a perfect negative correlation

Here we would find a perfect negative correlation (-1.0) between the age of subjects and their test results. An age increase of two years of a participant is related to a decrease of the number of correct observations by one unit. Even though the relation, i.e. here the said correlation, is obviously realistic in its tendency, we would hardly find this strong and direct relationships between these variables in reality. In this example, when evaluating the reliability, or more generally, the quality of an instrument, we should make sure that the particular psychological phenomenon is defined precisely and that the test constructed to measure it probes the construct or concept reliably and validly. Tests have usually been constructed in an circular iterative process, where different versions of the test are piloted, modified and that way made more precise. When a test gives us a zero correlation between two variables, or a value that is according to certain statistical criteria so close to zero that it does not effectively differ from zero, we state that these variables are independent of each other. In these kinds of situations, we cannot predict the change in one variable using the information about the other variable. Even though the correlation, that is, the covariation between the two variables, was greater than zero, we could not presume that the level of the variable used to predict the change in the other variable would predict real-world changes in that phenomenon.

For instance, we might very well find out that statistically - but not causally - monthly variation in ice cream sales in Finland explains the variation in the number of deaths due to drowning. Still we could not prevent people from drowning by reducing ice cream sales. There is no causal, i.e cause and effect link between these phenomena, but there is a third factor, or better still many factors, behind the apparent causal relation, one of them being monthly changes in temperature. When studying relationships between psychological constructs that correlate, we should still be able to explain their covariation by some scientifically valid mechanism, while controlling for the potential effects of so called intervening or confounding third factors. Additionally, in order to prove a causal relationship the cause should precede the effect. It is rather common in psychology to see that these mechanisms (theories, models, laws) become understandable by reasoning alone.

Factors affecting the evaluation of reliability

Especially where human behavior is concerned it is essential to note that even when measuring a well-defined phenomenon (e.g. anxiety, working memory capacity, extraversion) with a valid psychological test instrument, test results will be composed of two parts. On the one hand, a test result represents true nature or the level of the measured quality, state or characteristic, and on the other hand the results include error variance that is brought around by various random effects. When evaluating the reliability of measurements, it is worth understanding that there will be random variation around the measured levels of certain constructs between measurements in the same subjects due to changes in other factors such as motivational states, vigilance or moods. It stands to reason that these changes will affect the phenomena of research interest, because they will modify the way a research subject relates to test items or to what extent the subject is motivated or able to complete various tasks. Certainly concrete test circumstances affect the way people relate to different tasks, as well.

Even when certain detrimental pathological states and changes are left out of consideration, the human personality is known to change over time due to maturing and learning, necessitated by the environment, or rather environments (physical, social, cultural) where the individual operates and tries to survive. These processes are facilitated by the plasticity of human behavior, the biologically mediated ability to model and command an individual’s environment, while there is variation also in this ability. In some individuals this ability is stronger than in others, meaning that we find individual differences in the ability to learn, and also in general cognitive abilities. Intelligence is very much a value-laden concept. Usually only certain domains of intelligence - such as mathematical-logical, linguistic and spatial-perceptual - are lifted up in discussions, whereas the term general intelligence is defined as an ability to readily apply learned skills, adapt to new situations or as an ability to comprehend and utilize abstract concepts. Another definition states that intelligence shows in an individual’s ability to act rationally and purposefully in a new situation on the condition that this behavior is not based solely on previous learning.

When studying intelligence the ideas of purposefulness, motivation and values have to be accounted for. The quality of intelligence assessment instruments should preferably be studied in designs that control other so called confounding factors, using well-designed problems and clearly defined criteria of the studied cognitive processes (i.e perceptions, thinking, memory, decision making and guidance of one’s own behavior). The personality changes at a micro-level also when innate aptitudes and talents of an individual are refined and ennobled through a process of learning. Temperament is a more stable background, setting certain limits for personality development while also enabling and guiding this process. For these reasons, it is understandable that when assessing the reliability of a psychological test instrument, the time interval between the measurements that is needed can not be so long that research subjects might change in the above defined sense of maturation and learning. Anyhow, in many cognitive tests this interval should be long enough to prevent the subjects from responding to test items solely because they learned to solve these specific problems having dealt with those once before. In psychology this kind of learning effect is called the carry-over effect.

It may also happen that a person does better or worse in an ability re-test just by chance. We refer to this phenomenon as regression towards the mean. Among persons who do better than average in a cognitive test there will be some whose real performance level is below average. The factors behind this effect may be e.g. mood, a good night’s rest or proper preparing for the test. On the other hand, among those who do worse than average there will be individuals in whom those factors are unfavourable in that particular test situation. In other tests these persons might do better and their results would be closer to the average. That is why we say there is regression towards the mean. There is another noteworthy factor that is more difficult to control and whose effects should be taken into consideration when evaluating and interpreting ability test results. It has been shown that such personality features as emotional reactivity, stress tolerance, introversion and conscientiousness may cause individuals in whom these features cumulate towards opposite ends of the continuums to achieve on average very different test results just because of these personality traits. These differences should not be interpreted solely as indicators of differing work performance in real work conditions, even if the very tests were developed to help predict performance under those conditions. We know that cautious and conscientious introverted persons often prove to be a very competent employees in many tasks once they have accustomed themselves to those practical working conditions that may initially have appeared unfavourable to them based on some tests used to predict work performance. Still, there are other kinds of positions where continuous changes and various distractions prevail in the working environment. Tests simulating these kinds of environments may better predict success in those work positions. When improving criterion validity we try to find methods to increase the practical predictive power of tests.

Psychological constructs and reliability

When the value of Cronbach’s alpha, a commonly used indicator of internal consistency of tests, is very high in a test instrument, it is possible to make two very different inferences about the test. The situation is unproblematic and in many ways ideal, if the measured phenomenon is clearly defined and as long as the extension or referent (the area of reality the operationalized instrument is supposed to represent) is clear-cut and embodies little variance. Examples of these kinds of psychological aptitudes are spatial perception and numerical ability, as usually tests used to gauge these abilities demand using rather narrow span of cognitive resources - in relative terms, that is. On the other hand, we might justifiedly suggest that it may be problematic if an alpha value exceeds 0.90 for operationalized concepts that do not relate to such mathematically and logically precise mental representations or intentions, but that relate to more fuzzy, qualia-like experiences. Instruments with very high Cronbach’s alpha values may not measure the whole range of these kinds of concepts. We also know that by increasing the number of test items the value of Cronbach’s alpha increases, while this inflation may not improve the real consistency of the instrument. Adding test items after a certain threshold improves spurious consistency of a test. Mindfindr competence measures consist of 4 -7 items. Competences are such features and strengths of an assessed person that may have differential relevance for well-being, success and development at work in different sectors and professions. Competences are based on the personality, aptitudes, motives and interests of the individual. Competences are known and also scientifically shown to correlate with results of more traditional aptitude tests. The three aspects of the concept of competence - ability, interest and practical experience - make the competence profile of Mindfindr a comprehensive tool for assessing an individual’s practical work performance and well-being at work.

The Mindfindr competence test for measuring logical-mathematical aptitude has Cronbach’s alpha values that vary between 0.88 and 0.89 according to three different samples (n = 144, 298, 301). On the other hand, for the competence dimension of intuitiveness the Cronbach alpha is much lower, at 0.67 according to three samples (n= 144, 298, 301), obviously partly due to the certain essential fuzziness of the competence. On average, the mean of the Cronbach’s alpha values for all Mindfindr competence potential measures vary in the range 0.79 - 0.81.

Especially where well established personality test instruments are concerned, there has been a tendency to search for a balance between reliability and the number of test items on the one hand and between usability and efficiency on the other hand. One central aim of test development is to optimize the internal consistency of the test items without compromising the coverage of the studied phenomenon in its entirety. It may not hence come as a surprise that the split-half reliabilities of the Prf personality inventory (Personality Research Form), for instance, vary between the values of 0.48 and 0.90 with the median at 0.78 (Spearman.Brown; n=192). The same figures for the most widely used personality instrument, the NEO-PI-R range between 0.50 and 0.87 with the median of 0.77 (n=132). It is noteworthy that the internal consistency of instruments is not very sensitive to the sample size, unlike in the case of validity testing. The internal consistency of The Culture Fair Scales developed by Cattell is 0.78.

The stability, reliability and repeatability in testing - test-retest reliability.

The reliability of a psychological instrument is assessed using test-retest reliability when it is possible to test the same persons twize and optimally in the same or very similar test conditions. This procedure gives information about the extent to which the test instrument produces reliably similar results when data is collected under similar conditions from the same test subjects.

It is worth noting that when measuring human behavior the interval between these measurements should be long enough to presume that the test subjects may not reproduce their responses based on learning from the first testing alone. This notion is very important especially when evaluating the reliability of instruments that are used for assessing cognitive abilities. If the very same persons take the same, or similar tests again there will be a learning effect, or a so called carry-over effect affecting the results positively in the latter test. This poses a more general problem for the assessment of cognitive abilities, as the meta-logics in various tests may often be rather similar.

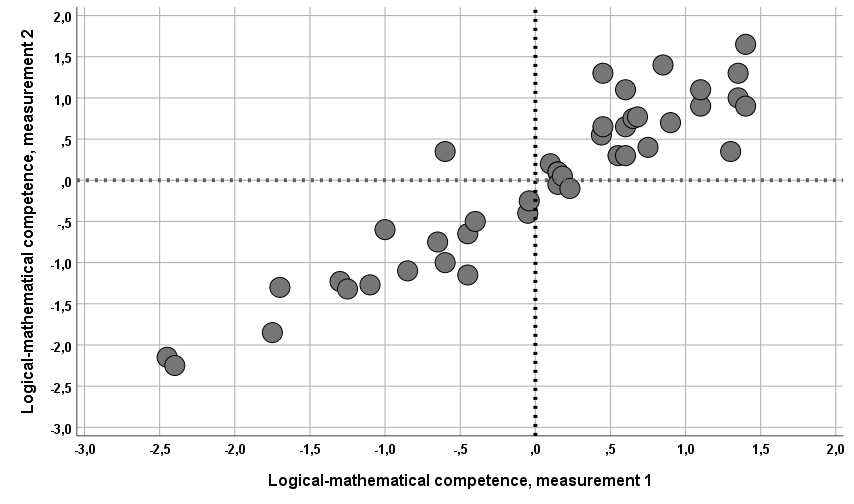

In a sample of disinterested persons who took a Mindfindr test twice with an interval of ca two weeks (median=19 days, range 11-37 days) in between, the test-retest reliability in mathematical-logical competence dimension was 0.907 (n=31). The convergence validity of this dimension is discussed later in the text.

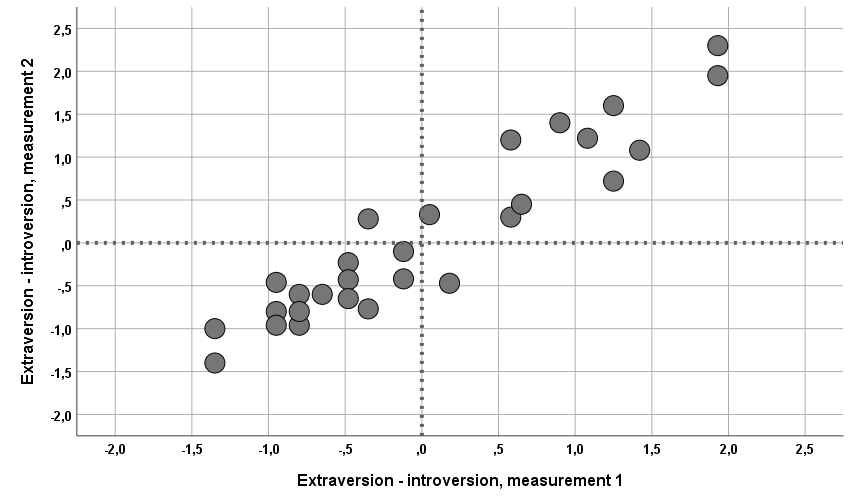

The value zero thus shows the sample means of measurements in both tests. In another study (Figure 4) a sample of persons who had completed an upper secondary education with a mean age at 23 years took a Mindfindr test twice with an interval of 6 months. The study subjects were applying for a training and the first test results gathered were used to assess their suitability for the training program. The second set of test results were collected when the persons had started the training program. In this sample many of the factors usually affecting test results were different in the first and second test sessions. Not only the season of the year was different (early autumn vs. middle winter), but also the interests of the testees had supposedly changed. Whereas the first test was conducted under stress related to performance pressures as part of long entrance exam days in supervised locations, the other set of data was collected in leisure time and obviously without pressures usually related to competition. The test procedure and the times for completing the items were the same, though. The test-retest reliability was 0.932 (n=42, figure 4).

Despite the obvious reduction in variance (the sample consisted of selected applicants only) it is possible to roughly evaluate the exactness of the competence measurements at least regarding the relative strength of those below and above the average level of the sample. However, there is one person whose first test result was among those below the average (below the zero on the x-axis) but the latter test result of this subject was above the zero on the y-axis. For comparison, the immediate retest (both tests taken the same day) reliability of Cattell’s Culture Fair Scales, one of the gold standards in intelligence research area, was at 0.84. For the Scale 3 of the battery the retest reliability with a time interval of one week at most was 0.82. To further compare, for The NEO-PI-R personality test, one of the most used versions of the FFM (Five Factor Model) tests, test-retest reliability with one week time interval in sample consisting of university students was 0.83 (n=132).

Personality assessment and Mindfindr

When evaluating reliability of research results it is worth remembering that with the increase of time between two measurements needed for reliability calculations, the risk of occurrence of factors affecting the response style of research subjects increases as well, and this effect also changes between the subjects in uncontrollable ways. The figures for the retest reliabilities of Mindfindr personality dimensions are usually lower than for the test component measuring logical-mathematical competence potential. However, this is not the case with the dimension measuring extraversion that is comparable construct to those defined and predicted, for instance by various FFM tests, The Prf and The MBTI instruments. The retest reliability of the Mindfindr extraversion dimension in the above described well-controlled sample was 0.945 (n=31). The disinterested group completed the tests anonymously in the same conditions with on average 20 days between the measurements (figure 5). The mean age of the subjects who had completes upper secondary education was 22,3 years. The test-retest reliability of all the Mindfindr personality dimensions was 0.90 in the study. The second strongest retest reliability was found in the dimension that is comparable to structure (The Prf) and conscientiousness (FFM instruments) (0.915; n=31).

Validity - exactness of instruments and appropriateness of predictions

We can discern several approaches to the validity of a psychological assessment instrument. Some of these are:

- Content validity

- Criterion validity

- Construct validity, which may be further broken down into

- Convergence validity and

- Discriminant validity

Besides these rather technical aspects of validity considerations an assessment instrument may be said to have good face validity. This means that a layperson is able to see by reasoning alone that the method measures aptly what it is supposed to measure. Face validity is not judged by particular technical criteria but usually any person who is familiar with the area of study in question is able to evaluate the face validity of an instrument. However, face validity does not inform us about, for instance, to what extent the instrument covers the conceptual domain of the measured construct. In the same vein, we cannot know if a face valid instrument yields similar results when compared with other instruments measuring the same construct. As all psychological instruments have their specific error variance sources, no one instrument is considered the only or the best test instrument. Consequently, usually many different instruments are utilized in practical assessment work, and interviews should always be included in any assessments.

Content validity

Good content validity means that the items, any kind of questions or problems comprising an instrument, cover as comprehensively as possible the conceptual sphere or domain of the measured construct. In philosophical terms this entails that the empirical domain of the construct has been successfully operationalized so that the items link the construct with observable reality. A substantially valid instrument encompasses the essential practical meaning of the measured construct. Earlier in the text the dilemma of striking a balance between the internal consistency and reliability of instruments was discussed in passing. Content validity may become somewhat compromised if the internal consistency of the instrument items is overly emphasized. On the other hand, instrument developers cannot ignore the practical usability and efficiency of assessment instruments. In the development of the Mindfindr service, this challenge has been approached with content validity in mind, especially where the competence assessment components are concerned. The idea has been to model various competence profiles in a way that accounts also for motivational aspects besides natural abilities and acquired skills. In an iterative development process the items of competence components have been been selected that represent the constructs most efficiently.

Criterion validity

In psychology the strictest definitions of criterion validity stipulate that by using the instruments we should be able to predict future behavior of assessed persons. In the area of suitability assessment this means that we aim to predict the work performance and success of the assessed persons in the work positions set as criteria. Criterion validity studies pose several challenges for test developers. When producing assessment and selection services for client companies it is difficult to acquire empirical information on the later work performance of the selected persons due to labor code, confidentiality clauses regulating the use of collected data and organizational practises. On the other, even if this information was available, usually only a few persons or a tiny proportion of first stage candidates in selection processes are selected for the positions that were set as assessment and selection criteria. Those screened out do not end in those positions and hence such information of their performance that could be compared with the performance of those who were selected will not be available. However, if the group of those ultimately selected is larger, it may be feasible to use performance assessment data collected (e.g. at time 1 and 2) when the persons have worked in the posts and model that information using the original selection assessment data (at time 0) to later explain any potential variance in the work performance scores. The problem caused by reduction in variance that was discussed above poses particular challenges in this approach, though. When we have first selected the persons who best meet the selection criteria it is obvious that there will not be very great differences in the most important competencies among the selected. This means that it will be difficult to find great differences in the critical variables that were used to find the best candidates. From the viewpoint of a recruiting organization this is hardly a problem.

Comparing persons who have worked in a position for a long time with newcomers into the field is not without challenges, either. There are differences in how readily people learn and adapt to new circumstances, but usually those having started first will have more practical knowledge of the central tasks in any job. Selection criteria may be produced by asking so called substance matter experts (SMEs) list the competences they consider the most important in a position. SMEs having themselves worked successfully in the same or similar positions are well-equipped to help define selection criteria based on their practical understanding of the particular work tasks. Other SMEs may have functioned as leaders or developers in the line of work to be defined and specified. A bit more straightforward way is to collect criterion validity research data from larger groups of research subjects if such are available. These subjects will have to be assessed, scored and ranked by persons who know them professionally and can objectively assess them. One advantage in this kind of procedure is anonymousness that is likely to facilitate the acquisition of more unbiased assessments by the scorers and also more straightforward and frank answering to test items by the research subjects. Often these processes involve the use of practical work simulations as assessment criteria.

This procedure is helpful in the development of criteria-based assessment instruments, while it is not immune to some of the above-discussed challenges related to validity assessments conducted with persons that have already been selected for certain positions.

Construct validity

Construct validity may be divided into convergence validity and discriminant validity. Convergence validity studies focus on finding out to what extent the tests that are evaluated for their validity give similar results with other, usually somewhat more established test instruments which are known to measure the same or very similar constructs. In practice good convergence validity shows as a strong correlation between the two instruments whose convergence is under scrutiny. Discriminant validity describes to what extent an instrument measures and predicts just the construct it is developed to measure and not something else. However, in psychology and especially in the domain of personality research we see that many personality dimensions may correlate with each other rather strongly in a logical and understandable way. To take an example, when studying intuitiveness and creativity as personality features, we often find that strong intuitiveness and openness to experience are related to rather strong flexibility and adaptability. It stands to reason that creativity and innovativeness presuppose certain amount of openness, imaginativeness and the flexibility of mind, these enabling a person to approach things from different and novel perspectives. On the other hand, when a test is supposed to measure a person’s logical-mathematical abilities, it should not correlate very strongly with other cognitive ability measures. Likewise, a test gauging the ability to figure out spatial structures should optimally not correlate with linguistic aptitude test results more strongly than with spatial-perceptual ability test scores. However, general cognitive aptitudes, often referred to as fluid intelligence, allow one to reason and solve problems in new situations, this affecting to an extent one’s performance in various test domains measuring cognitive abilities.

Table 2 shows some convergence validity research results conducted on the Mindfindr competence dimensions based on correlations with other cognitive ability tests.

| Mindfindr-competence measures | Comparison with AVO-tests | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mindfindr | Logical-mathematical | Linguistic | Spatial | AVO/R1/R3 | AVO/V3/V5 |

| Culture Fair Scales | .523 n=96* | -.067 N.S. n=96 | .201 p=.05 n=96 | R1.484 n=96 | V3.343 p=.001 n=96 |

| .417 n=77 | -.128 N.S n=153 | .220 p=.01 n=127 | R1.303 p.007 n=78 | V3 .390 n=158 | |

| .383 n=127 | .152 p=.06. n=153 | R1 .378 n=158 | |||

| .354 n=153 | V5 .232p=.04 n=78 | ||||

| .307 n=151 | R3.453 n=78 | ||||

| V3/V5-AVO-test | V3 .437 n=285 | V3 .290 p=.004 n=96 | R1/V5.349p=.001 n=81 | ||

| V3.318 p=.002 n=96 | V3 .149 p=.003 n=392 | R3/V5.333p=.002 n=81 | |||

| V3.195 n=392 | |||||

| V3.256 p=.001 n=151 | |||||

| V5 .198 N.S. n=80 | V5 .03 N.S.n=80 | ||||

| R1/R3-AVO-test | R1.493 n=96 | R1 & R3 N.S. n=80 | R1/R3 .534 n=81 | V3/R1 .476 n=96 | |

| R1.307 p=.006 n=80 | V3/R1 .423 n=418 | ||||

| R1.167p=.001 n=392 | |||||

| R3.381 n=80 | |||||

| S2/S3-AVO-test | S2 .255 n=343 | S2 .257 n=343 | S3/R1 .267 n=418 | S3/V3 .350 n=418 | |

| S3 .317 n=127 | S2.168 p=.001 n=301 | ||||

| S3 .300 n=392 | S3 . 221 n=392 | ||||

| Number series test ** | .391 n=343 | .009 N.S. n=301 | .030 N.S. n=343 | ||

| .475 n=469 | |||||

| .482 n=285 | |||||

| .442 n=151 | |||||

| .402 n=301 | |||||

| Logical inference test ** | .326 n=343 | -.006 N.S. n=301 | -.063 N.S. n=343 | ||

| .297 n=469 | |||||

Table 2. Convergence validity between Mindfindr and other instruments

* p< .001 if not otherwise reported

** Culture Fair Scales correlate with a number series test (e.g. 0.355; p=.000; n=128; 0.338; p=.000; n=133) and with a logical inference test (0.424; p=.000; n=128; 0.398; p=.000; n=133).

In the table 2 it is possible to assess general discriminant validity aspects of Mindfindr. For instance, the results of the Culture Fair Scales (CFS) correlate with other measures of general cognitive ability. The results of the CFS converge especially with logical inference tests (R1, R3) but also with linguistic tests (V3, V5) the latter of which requires comprehension of semantic-logical relations and conceptual nuances between words. The Mindfindr logical-mathematical competence dimension correlates rather similarly with the same tests, especially with the CFS, logical inference tests and the number series test. On the other hand, the spatial perceptual competence dimension of Mindfindr correlates with the spatial tests (S2, S3) but not with the CFS, general logical inference tests or the number series test, thus showing good discriminant validity in this respect.

Personality and construct validity

Until the turning of 1990’s there prevailed numerous personality theories each approaching and explaining the human personality from somewhat different standpoints. Since then there has been a consensus according to which the personality may be understood as a combination of five meta-dimensions or factors. This general model is called the big five, or the five factor model (FFM). The first versions of the model were constructed on the so called lexical hypothesis, basically stating that natural languages had evolved to describe all phenomena that have relevance for human behavior. It was further postulated that natural languages also cover all adjectives needed to comprehensively describe human personalities. The five personality factors that the scientific community deems as universally describing basic personality dimensions are as follows:

- Extraversion, social inclination, activity

- Openness to experience, imaginativeness, creativity

- Agreeableness, friendliness, personal warmth

- Neuroticism, negative emotionality, emotional stability

- Conscientiousness, punctuality, orderliness

When information on an individual’s cognitive abilities are combined with data about the above dimensions it is thought that we get a general idea of the individual’s personality. The dimensions of extraversion and openness to experience are thought to represent a more general axis of the plasticity and adaptability in the personality, while low negative emotionality and conscientiousness describe a person’s stability. Many extensive studies have proven that the five factors may be rather reliably used to predict a person’s work performance. It is known that general cognitive abilities and conscientiousness combined predict a person’s success in studies and at work in the long run on average quite well.

Motivation as a personality domain

Along information on an individual’s personality features it is important to take into account motivational factors when predicting the future work performance and also well-being at work. In optimal situations an individual should find such a position in working life that facilitates his or her flourishing, to use Martin Seligman’s terms. This means that the person finds the tasks in the position challenging enough while feeling that one is able to contribute to values and aims that are meaningful and dear to oneself. Ideally motivating work also enables one to further develop one’s competencies and skills. The RIASEC model developed by Holland is a useful tool for finding out which occupations and professions might optimally inspire and enable an individual to utilize one’s motivation at work.

The model covers the following six dimensions:

- R = realistic

- I = Investigative

- A = Artistic

- S = Social

- E = Enterprising

- C = Conventional

Occupational guidance work has shown that the information yielded by the RIASEC model correlates with results from some other personality tests, like the MBTI, as these both gauge a person’s preferences and interests very pragmatically.

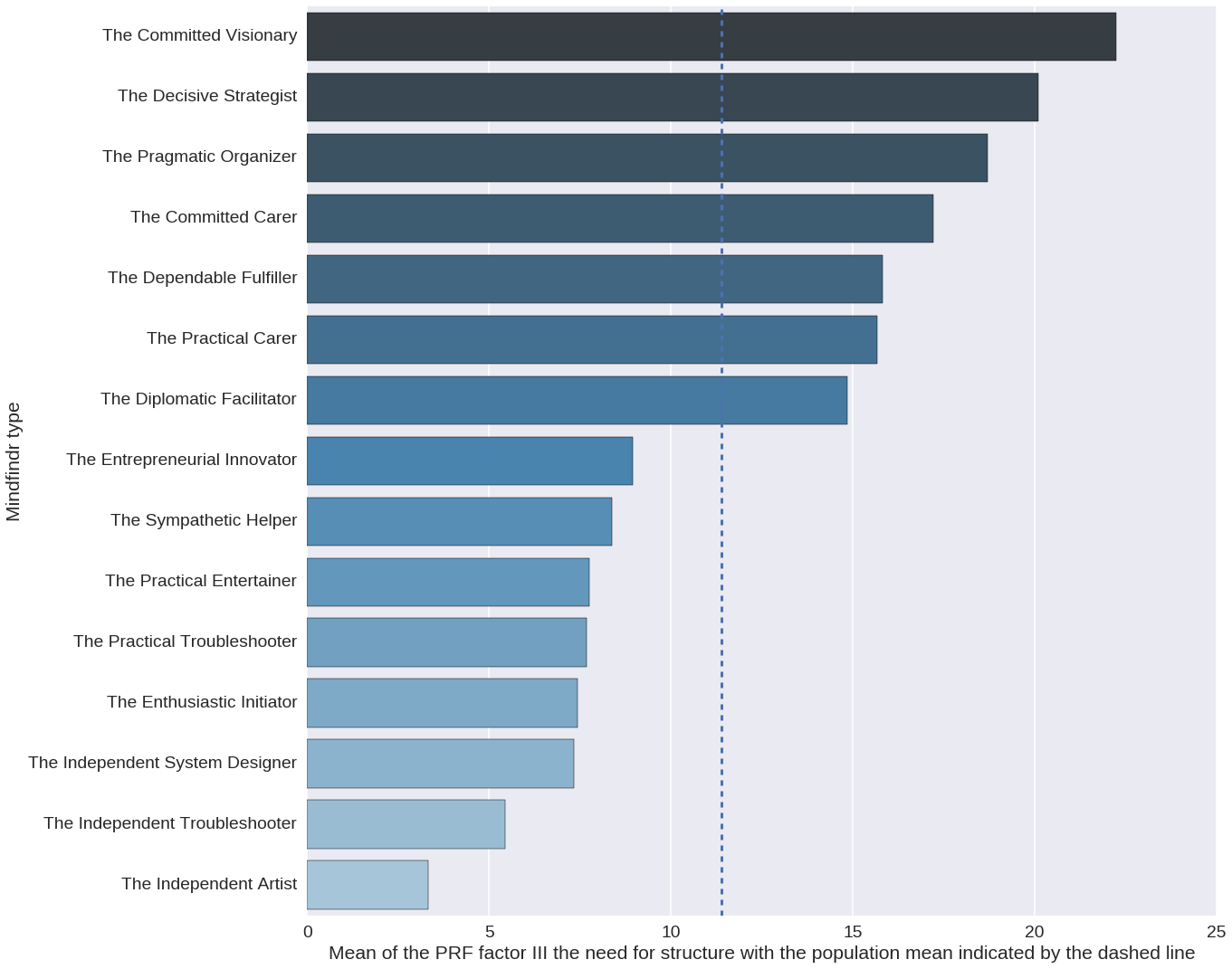

The convergence between the Mindfindr and the Prf dimensions measuring conscientiousness and planfulness seen in the figure 6 was 0.651 (n=623). In another sample the comparable correlation was 0.682 (n=466).

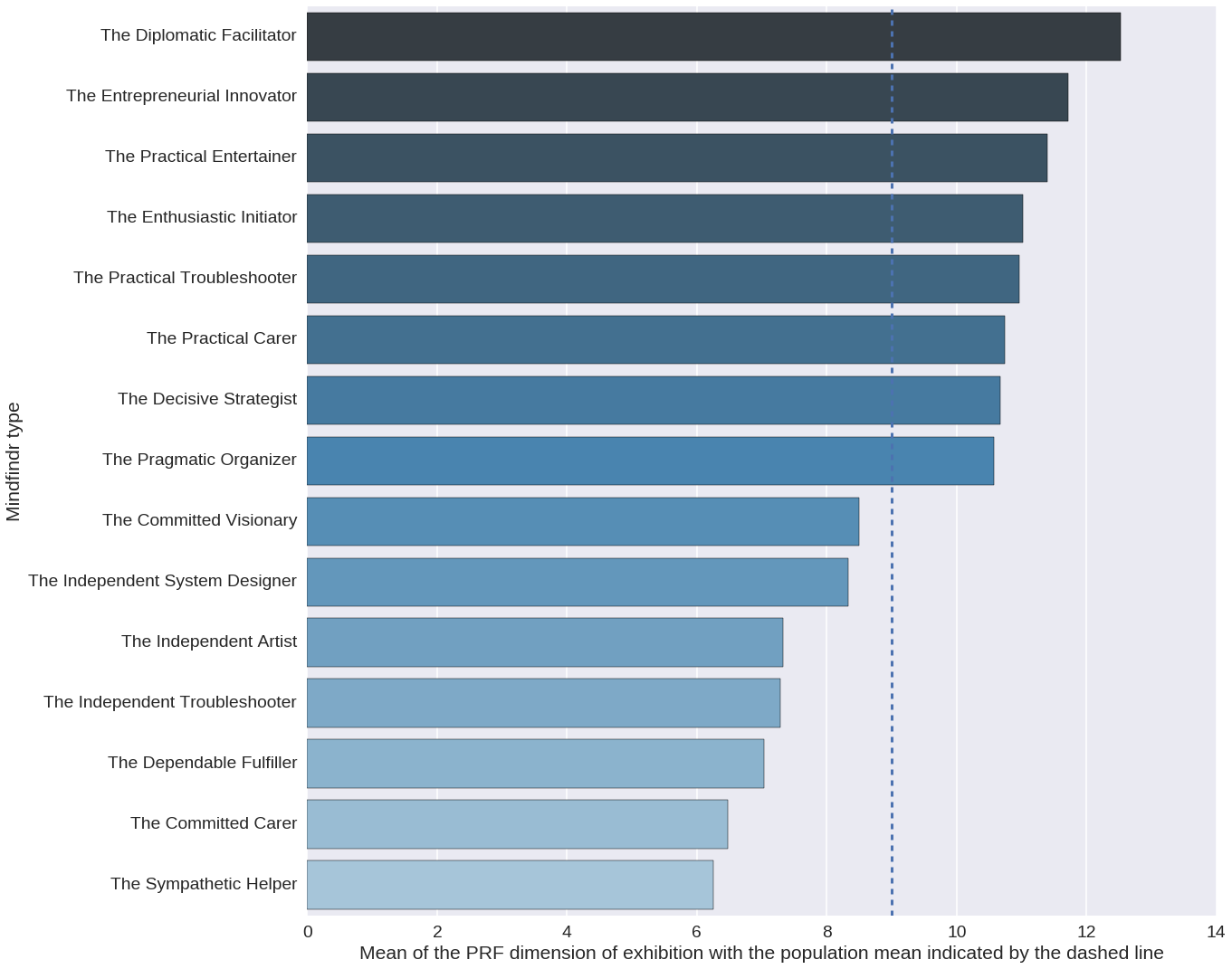

The table 3 and the figure 7 show the level of exhibition as measured using the Prf in different Mindfindr personality types. The convergence correlations between the Prf measurements of exhibition and the Mindfindr measurements of extraversion, activity and sociability are shown in the table 3.

Table 3. The convergence correlations between the Prf measurements of exhibition and the Mindfindr measurements of extraversion, activity and sociability in two samples.

The figure 7 shows that those Mindfindr types that are according to the method on average more introverted than extraverted have scored below the mean of exhibitioness in the Prf. On the other hand, those personality types that like to work e.g. as teachers, educators, politicians and entrepreneurs have scored on average above the population mean of the dimension. For instance, practical performers, who excel in performing arts and occupations requiring strong social presence have on average scored very high on the dimension. Enthusiastic initiator types shine naturally as actors, as well. The development process of the Mindfindr service has been informed also by the MBTI method. While not enjoying unreserved respect among academic psychologists, the method is possibly globally the most widely used personality instrument in practical leadership coaching processes. Possibly just because its pragmatic approach. The roots of the MBTI instrument may be traced back to the ideas presented by Carl Jung almost a hundred years ago. Nowadays the best known dimension originally presented by Jung, extraversion vs. introversion and the respective types (introverts and extraverts) were later validated in modern personality psychology.

Below are two examples of correlations between two dimensions measured using the MBTI and the NEO-PI instruments

| MBTI | NEO-PI | Convergence | Signifigance | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraversion-Introversion | Extraversion | -.74 (men) | p<.001 | 267 |

| -.69 (women) | p<.001 | 201 | ||

| Judgement-Perception | Conscientiousness | -.49 (men) | p<.001 | 267 |

| -.46 (women) | p<.001 | 201 |

Table 3. Correlations between dimensions measured using the MBTI and the NEO-PI instruments

The development of the service

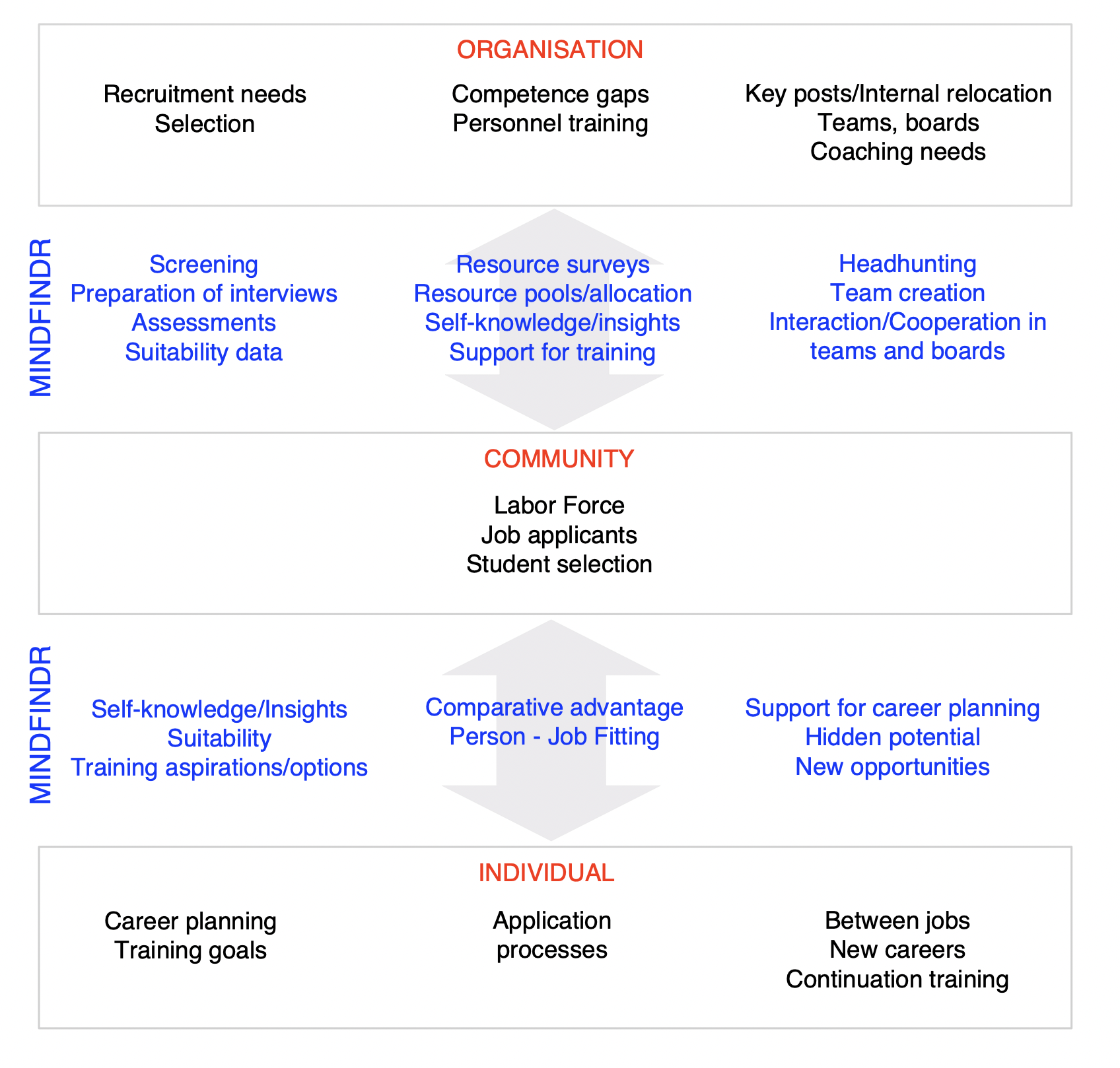

The development of the net-based assessment service started in the summer of 2014, and the team of current developers founded Mindfindr Ltd later that year. In practise the development has proceeded along the lines of combining some aspects of more traditional assessment methods with service solutions adaptable to the grid. The service allows test organizers to create assessment projects, invite participants, process all assessment data and utilize reports real-time in the net. There are various optional ways for organizing tests and sending invites to testees. The figure 8 shows how the service solutions enabled by Mindfindr serve technically somewhat different but in the end mutual interests of companies, individuals and the public sector. From the perspective of the individual the service allows finding solutions to education, training and work-life related challenges over the lifespan, while facilitating recruitment and HR-development processes by which companies find and further develop the competencies their production processes require. In helping to increase the compatibility in the spheres of demand and supply, the Mindfindr service solutions improve the employment level and overall activity in the economy. Due to swift changes in working life individuals may find themselves more than once between jobs over their active years and in need of redefining themselves and finding new careers. This is where Mindfindr comes in handy, helping individuals who already know something of their competencies to find where to put those strengths in profitable use or which areas to develop to be better equipped to start completely new careers. Obviously Mindfindr facilitates also long run planning in such between jobs situations, where there is next to no clues about where to head in the labor market. The same goes for the youth, of course.

Where client companies are concerned, Mindfindr is especially useful in sectors where on the one hand may prevail a great turnover of employees or on the other the required training levels are moderate at best. In these market circumstances it is smart to utilize light and pragmatic methods that produce assessment data and reports in a cost-efficient way, online and in real time. In more intensive processes Mindfindr yields multifaceted information on any candidates, helps put up and strengthen teams and even boards by finding out where the weak spots or gaps may lie in an organization or a team.

In recruitment processes Mindfindr facilitates the preparations for interviews by lifting up potential challenges to be cleared for instance by checking the references or requiring further attention in interviews. Mindfindr ranks the applicants in processes and yields a general overview of the applicants, or serves as a general background data to be complemented with more extensive assessment centre solutions. Similarly, an organization may utilize Mindfindr to ascertain that the critical competencies are well presented in the right positions in the company, or to fill in any strategically important competence gaps by recruiting. Even at the level of exe boards it may happen that there are only certain kinds of personalities that understandably get on well together, this state of things potentially leading to unwanted groupthink phenomena likely to stagnate development. Yet more generally, Mindfindr may be used in any coaching processes, also outside the business and work life. Most models of goal-oriented coaching recommend starting with assessments and tests that show where the coachees are with regard to their aims and aspirations. Another very basic rationale is to increase the self-understanding of the coachees. An organization’s own cumulative Mindfindr data pool facilitates finding the best candidates for any positions according to the specified 350 + occupations and professions in the service. This is especially helpful in situations where an organization may have to relocate persons who might otherwise become redundant due to changes in tasks.

Introduction to the components of Mindfindr reports

Basic reports

Personality description

A personality description produced by Mindfindr focuses on such personality traits of the assessed that are considered relevant to work performance. The description is based on a combination of five personality dimensions widely shown to be scientifically valid. An assessed person may also be attributed two somewhat different personality descriptions should the results warrant that. The profile describes general work behavior typical of the assessed. In addition, the profile information covers such areas as interactional and teamwork styles, as well as special strengths and challenges of the person. The report also covers likely developmental challenges typical of the personality features of the assessed where relevant regarding success and wellbeing at work.

Occupation specific suitability estimates

Occupation and profession specific suitability estimates are based on the information provided by the assessed regarding their personality features, competences, work style and leadership potential. When modeling and estimating the suitability of the assessed these strengths and interests are combined with work definitions presented e.g. in the ISCO categorization system, while interest structures defined by Holland are also included in the modeling. When used to facilitate career planning, the consultant and the assessed person may decide which level of training to choose to go through listed occupations and professions. Regarding recruiting processes occupations and professions are categorized in 7 classes according to typical minimal training requirements. It is important to note that even if the applicability and relevant competences of a person were assessed as being very modest or low for a particular position, he or she might be very suitable for other positions. Mindfindr analyses and differentiates in a complex fuzzy process between various competence potentials relevant for any given position as well as the corresponding desired qualities (e.g. personality, abilities, leadership qualities) evinced by the assessed person.

The structure of competencies

The competence potential profile describes the structure of a person’s competencies or abilities relevant to work-behavior. By the term competence profile a reference is made to a combination of abilities a person recognizes, and of which the person has some experience, having utilized the competencies, skills and capabilities in practice, and which the person is willing and motivated to avail him or herself of at work. The competence potential of a person may more or less correlate with the relevant performance criteria for different positions and occupations, thus forming the developmental potential the assessed person may already have strengthened and improved through relevant work experience or formal training. The Mindfindr competence model is based on ten key competencies relevant to work behavior and work-satisfaction related work environments.

Extended reports

Working style

In a work style description the work style of an assessed person is depicted using 10 work style dimensions. These enable evaluation of an assessed person’s work style to consider to what extent the person is likely to meet the requirements of a given position when defined using the 10 work style dimensions that are listed in a table. A practical work style is partially based on the personality, competencies and preferences of an assessed person. However, it describes the work style of a person more concretely. The work style description covers such dimensions as punctuality, initiative, sociability, influence and analyticity. The work style profile will yield practical information on the person’s concrete work performance. Team compositions, organizational cultures, or particular needs of clients may affect which work style profile meets various requirements of clients best or optimally complements a team.

Team work style and team roles

Different models of team structures give various numbers of team roles. The Mindfindr model covers eight different team or group roles. These are such as the inspirer, the finisher, the organizer and the analyst. Special contributions brought through each role into teamwork as well as an assessed person’s relative strengths in various team roles are depicted in a graph. Additionally, three strongest roles are highlighted as the most suitable ones for the assessed. Team analysis information may come handy in many ways: when creating a new team through recruiting or when considering sharing responsibilities and ascribing roles among an executive board. In coaching a team role analysis may help improve communication through providing a deeper mutual understanding between team members. Similarly, the analysis may be used as a tool to approach and resolve communication problems in organizations.

Leadership analysis

The Mindfindr leadership analysis covers three levels. A general leadership potential estimate gives a rough estimate of a person’s inclination to leadership on a five level scale. Additionally, an assessed person falls into leadership type categories. These are process leadership, results-oriented leadership, developmental leadership and change leadership. The third aspect substantiates and further defines leadership styles of the assessed. These eight leadership styles include such styles as e.g. the strategic implementer, the inspiring coach, the emphatic maintainer and the participating supporter. The analysis may be used to gauge leadership qualities of a coachee at the start of a coaching process, or to find out what kinds of leadership perspectives are potentially underrepresented among an executive board. When considering a person’s suitability and motivation especially for leadership and managerial positions it is worth taking into consideration the person’s potential leaning towards various leadership and managerial styles, besides the overall estimate of the strength of this tendency.

Literature:

- Cattell, R.B. (1973) Measuring Intelligence with the Culture Fair Tests. Manual for Scales 2 and 3. IPAT, Inc..

- Honkanen, H., Nyman, K. (toim.). Hyvän henkilöarvioinnin käsikirja. Psykologien Kustannus Oy.

- Jackson, D.N. (1997) PRF Personality Research Form. Käsikirja. Suomenkielinen laitos: Petteri Niitamo, Työterveyslaitos. Psykologien Kustannus Oy.

- Kykytestistö AVO-9 Käsikirja. Ammatinvalinnanohjauksen faktoritestistö nuorille ja aikuisille (1994). Psykologien Kustannus Oy.

- McCrae R.R., & Costa Jr., P.T. (1989) Reinterpreting the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator From the Perspective of the Five-Factor Model of Personality. Journal of Personality, 57.

- Myers, I. B., & McCaulley, M. H. (1985). Manual: A guide to the development and use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Consulting Psychologists Press.

- PK5 - Persoonallisuustestin käsikirja (2007). Psykologien Kustannus Oy.